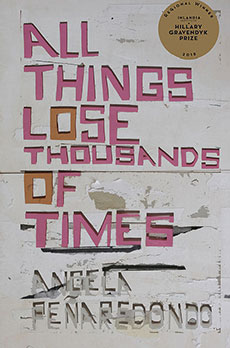

A Review of All Things Lose Thousands of Times

by Angela Peñaredondo

Riverside, California: Inlandia Books, 2016.

94 pages. $15.00 (paperback)

In her debut book of poems, All Things Lose Thousands of Times (winner of the Regional Hillary Gravendyk Prize), Angela Peñaredondo conjures up fantastic dreamlands of revolt and violent movement toward possibilities. Alternating between first-person lyric, second-person address, and third-person narrative, Peñaredondo disrupts Western narratives with dexterity and momentum while calling attention to displaced and marginalized bodies across nations and times. In the opening poem, “Another World Gathers,” the sleeping speaker describes herself as “a weak thing,” a “body down,” a dreamer willfully making herself vulnerable to bodies down past and present via channeling the other-within-the-self (19).

There is propulsion to this unconscious that combines a visionary urgency with a cinematic eroticism:

My eyes can do nothing elsebut stare at the way she grips

her father’s beard

as she leaves the office.

His head a sliver of meat …

So many women I know have it hard letting go.

The first woman I fell in love with,

all my fear inside my head. (29)

This poem, “Woman Leaves Psychoanalyst’s Office,” is based on a 1963 painting by the Spanish artist Remedios Varo, who worked within the orbit of Surrealists in Paris before she was forced into exile in Mexico City during World War II. Peñaredondo’s opening lines speak to the necessities of the desiring self, ever aware of its compulsions and limitations (“My eyes can do nothing else”). The dreamer as woman is not the hysteric of early psychoanytical discourses, but a wanderer and maker of queer spaces for people of color — a Baudelairian flâneur with a difference, as Mg Roberts points out in her introductory essay to the book. A Philipinx poet and artist, Peñaredondo operates as a transnational trickster negotiating the cultural and spiritual borders between the West and the global South, while grappling with the ethics of such crossings.

These are thinky poems. Letting go of patriarchal traditions and decolonizing the imagination risks psychic and material upheaval to both self and other. How does an artist confront her investments in traditions that exclude her? In “Mediation on Floating Above Sink Water,” the music of Strauss serves as counterpoint to the speaker’s questions about the violence of aesthetic practice:

Does the secret to great art lie between devotionand selfishness but with the radio

at Strauss’s Four Last Songs

you ask but what of sabotage

the other irrevocable

lined up and hung” (70)

Throughout the collection, Peñaredondo conveys a complex ambivalence about the legacy of Western male artistic figures, such as Joseph Cornell in the poem “He Who Knows Violence Is a Privilege”:

Through his shadowbox, I wantto reconstitute myself,

restore what was not enough. (69)

Melancholic musings shift into more ferocious assertions. In “As One of Egon Schiele’s Nudes,” a “hungry skeleton” emerges with “genitals flushed / to a liturgy of shrunken pulp” as if to obliterate the painting and aesthetic conventions which entrap her (62).

Divided into four sections, the book moves with a restlessness into the intimacies of such “hungry girls” (27). The lush incantatory lines of the poems become ritualistic offerings to the unsatisfied female spirits circling the book. And yet, these loving material details are still “not enough” to make up for the crushing disappointments of history, as suggested by titles such as “The Word Reality Meant Nothing to Her” (taken from Brazilian writer Clarice Lispector’s Hour of the Star, a story of a starstruck hungry girl with little food, money, or luck). Maybe the conditions have not yet arrived. But one can dream. And fantasy creates “real” effects!

Throughout the work, feminine longing itself generates possibility, multiplying desires and personas. For example, in “Self-Portrait As Mollusks,” the speaker advises:

And if you want loveand your hand on something

like a ripened thigh,

you must double yourself.

And who doesn’t like that? (75)

Here Peñaredondo’s pouncing lines echo Baudelaire’s “To the Reader.” But if Baudelaire reveals contempt for his bored readers and doubles (“Hypocrite lecteur, — mon semblable, — mon frère!”), Peñaredondo’s book proliferates with impassioned doubles and others who act with a sense of wonder, self-determination, and pain, dreaming of solidarity and belonging. Seemingly referencing the militant liberation struggles of the Tamil Tigers in Sri Lanka, “Black Tigers” is a thrilling tour-de-force, describing the actions of a young suicide bomber/freedom fighter with “a bomb strapped / between both breasts” in a country where “mothers / have turned into mangroves,” a striking image that expresses the insufficiency of contemporary fantasies of nation as a generative model of affiliation (26).

I found myself startled, tensed-up, living in and through these vivid, devastating images and personas. In the final poem of the book, “When the Saints Turned to Carnival Dancers,” the solitary dreamers and powerful spirits of the earlier poems appear to gather en masse to “throw themselves” with abandon “over the new world,” “as if shot from rifles,” momentarily united “in their cloths of celebration” (81). Even if Peñaredondo’s dreamers are “over the new world,” they hold out hope for other ones. They build and shatter worlds. They travel in between. They command, imbibe, dance, and love deeply. They are sexy, fierce, tender, and sublime.

about the author