A Review of Hold Me Gorilla Monsoon

Colette Arrand

Athens, GA: OPO Books & Objects, 2017.

61 pages. $11.95 (paperback)

1.

Hold Me Gorilla Monsoon is a poetry book about professional wrestling because Colette Arrand refuses any distinction between high and low culture. For Arrand’s speaker, wrestling is more than two dudes duking it out wearing just their briefs and a pair of boots.

Her poems portray and confront the ways masculinity is performed and learned through professional wrestling. They triangulate hypermasculinity, queerness, and homophobia in wrestling, conveying the painful experience of encountering these things as Arrand’s speaker comes to terms with her own trans identity. These poems are ambitious and dizzyingly good.

2.

The opening poem, “The Use of Roland Barthes to Justify One’s Love of Wrestling,” lets us know precisely what the book is about. Arrand begins:

My mother says that she hasn’t adjustedbecause she has no evidence of my womanhood.

My voice is still her son’s voice, my body,

however changed, is one she still pictures

as masculine. (13)

Arrand juxtaposes the mother’s inability to acknowledge the trans body with a story about the time pro wrestler Junkyard Dog was attacked by the Fabulous Freebirds and blinded with a handful of hair cream, which caused Dog to miss seeing the birth of his daughter. The blinding wasn’t real, but wrestling fans believed it was, which got Junkyard Dog over as a fan favorite and made the Freebirds the most hated men in the territory. The transition from the speaker’s story to Dog’s blinding isn’t seamless, but it doesn’t have to be — these are two stories of parents and their children, of believing what you’re told happened and refusing to believe the story unfolding in front of your eyes. This is the truth of both the relationship between the speaker and her mother and between wrestlers and their audiences.

3.

In his book Mythologies, critic Roland Barthes writes about “The World of Wrestling.” In one of the earliest dissections of pro wrestling as cultural artifact, Barthes describes how a wrestling match “demands an immediate reading of the juxtaposed meanings, so that there is no need to connect them” (18). The match doesn’t necessarily require that the viewer know anything about how a fight escalates into a bloodbath or how a wrestling hold works to incapacitate an opponent — a good match allows the viewer to understand and appreciate every moment without necessarily having to know how a moment fits into the narrative of the fight, or even into the overall storyline between the wrestlers.

In a similar vein, Hold Me Gorilla Monsoon does not require the reader to know anything about wrestling. There are poems about Hulk Hogan body slamming Andre the Giant, about Jake “the Snake” Roberts playing in a charity softball game, about the impracticality of Brutus Beefcake’s barber’s shears, and so many other well-known and lesser-known performers. However, these poems don’t rely on the reader’s knowledge of wrestling as much as they stimulate the reader’s senses and the imagination. The poems use these larger-than-life personalities to deliver their surprising heart punches. The storylines surrounding the Hogan/Andre match become entangled with the speaker’s estrangement from her father after he leaves her. The image of Roberts catching the ball becomes a metaphor for the way a life can be ruined and then resurrected. And the realization that Beefcake’s over-sized shears were just a prop becomes an acknowledgement of the ways that the speaker has hidden from herself.

4.

In a fight, a wrestling hold can subdue an opponent, and in the process cause great pain to whomever is being tied up. In a professional wrestling match, however, the person applying the hold is usually protecting the other from getting hurt. Scorpion deathlock, crossface chickenwing, surfboard stretch — holds like these twist the human body into all sorts of shapes, a display of pain for an audience, agony made beautiful for the viewer.

5.

The same can be said of the poems in Hold Me Gorilla Monsoon. Arrand accomplishes the difficult feat of writing poems that deliver the camp of professional wrestling, but does so in a way that diminishes neither wrestling nor the integrity of the poems themselves. On one hand, these poems are a romp through Arrand’s love of wrestling, and as such they are entertaining. But the poems’ beauty comes through their complex juxtapositions and surprising reveals of the speaker’s character. The book doesn’t provide a linear narrative of the speaker’s adolescence moving to adulthood as she starts to question her gender identity — that isn’t the point of this particular book.

Instead, the poems reveal a number of difficult truths about the speaker’s relationships to her family and friends, as well as the world around her. Take, for instance, “Executing a Pumphandle Slam,” in which Arrand describes how the move works: one wrestler “moves behind his opponent, bends him / forward, enfolds him” before lifting him onto his shoulder and smashing him to the ground. The speaker describes the awkward time her friend’s father caught them trying to do the move together: “He knows / what we are doing, has seen the slam / before, but with my cock against the curve / of his son’s ass, memory becomes / a foreign province” (20).

It’s an intimate moment, or perhaps it’s really only intimate for the speaker. But in that moment, there is a realization about how the physicality of wrestling means something different to the speaker than to her friend. Arrand writes, “Years before faggot / acquires a meaning I like to self-apply, / I know that wrestling is something faggots do / with their doors closed” (20).

Poems like “Executing a Pumphandle Slam” feature an unflinching gaze at the speaker’s self and her world as her relationship with the world refuses stability. These poems put the speaker’s pain and emotions on display for the reader, which makes for an uncomfortable reading experience at times, but then that’s kind of the point — there is nothing comfortable about a wrestling hold or struggling with sexuality or transitioning genders. Yet through all of this, the poems themselves are at their most elegant and beautiful when they are the most unflinching and unafraid of the reader’s discomfort.

6.

In Hold Me Gorilla Monsoon, all you need to know about the Great Muta is in the title of the poem: “For the Great Muta, Who, By Massaging an Extra Gland in the Back of His Throat, Is Able to Spray a Fine Poison Mist.” Here are a few things about Muta you don’t need to know:

- The Great Muta was a Japanese wrestler introduced to American audiences in the 1990s who painted his face like a demon and spit poison into the face of his opponent. Japanese wrestlers like Muta have used this poison trick for decades to blind their enemies and get a cheap win.

- There was no extra gland — it was just theatrics to explain the mist, which was probably really just Kool-Aid mix or some kind of food coloring capsule that Muta broke in his mouth when the audience wasn’t looking.

- In a match in Japan, the Great Muta once spit his green mist into the crotch of an evil wrestler who called herself Yinling the Erotic Terrorist. She became pregnant and laid an egg in the middle of the ring that hatched a 500-pound sumo wrestler.

- The Great Muta is the standard by which wrestling fans measure the amount of blood shed in a wrestling match. “The Muta Scale” is based on the heavy bleeding from the head Muta once suffered during a match after being hit with a foreign object. Of course, in reality, the head wound was self-inflicted for show, but the blood itself was real.

Pro wrestling is weird, and knowing a bit about the Great Muta’s career in the ring offers color and shock value to the poem in a way that might enhance the reader’s experience with it, but it isn’t necessary to understand the poem’s heart — the speaker’s relationship with her body. She tells her mother that she hates her penis and receives only her mother’s confused judgment in return. There is a longing in the poem, and throughout the book, to escape the human body into an unearthly one. Arrand writes:

If only my difference were as obvious as The Great Muta’s, a clutched

throat, a blinding green mist. I’ve often wished for an extra organ, something

tactile and sensuous. A piece of myself I could hide if it meant living pleasurably. (57)

There is great pain in these poems, and it isn’t pain from a wristlock or a steel chair to the skull. It’s a pain of the self, a pain of being separated from the self, of longing for a self that doesn’t yet exist. Or perhaps that’s impossible to ever exist.

7.

8.

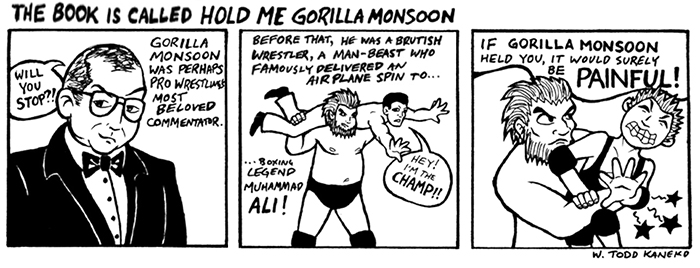

Just when you think you have all the answers, Colette Arrand changes the questions. The middle of Hold Me Gorilla Monsoon blisters with comic strips. Illustrated by Scott Stripling, these three-panel comics from Arrand’s web comic Wrestling School take us away from the textual world and into a visual one. The drawings are tough and gritty and the writing spoofs many well-known wrestling moves: the People’s Elbow, the Pop-up Power Bomb, the German Suplex — Arrand and Stripling play with them by playing with their names and spoofing the wrestlers who use them in way that conveys the pair’s great love of wrestling.

To fully appreciate these comics, a bit of knowledge about pro wrestling is necessary. For example, if you don’t know that the Tree of Woe is a wrestling move where one wrestler hangs the other upside down by the foot in the corner of the ring, the comic featuring the whiny tree might seem kind of random. Or without knowing that Kevin Owens has a son whose favorite wrestler is his father’s rival John Cena, the “Pop-up Powerbomb” comic might be hard to follow. But the real contribution the comics add to the book are their inclusion in what is otherwise a serious collection of poems. They provide a brief tangent away from the seriousness of the poems with a reminder that wrestling is supposed to be fun, and in the process further refuses the distinction between high and low culture.

9.

The poems in Hold Me Gorilla Monsoon cry out for comfort but the world of professional wrestling is more the realm of pain. Appropriately, the book’s final poem is an elegy for the late Adrian Adonis, a wrestler who spent much of his career as a tough guy wearing a leather jacket but is most well known for wearing heavy makeup and gaudy dresses, or as Arrand writes, “a wrestler ruined by his culture’s need / for someone to play the fag” (59). Arrand ends the poem, and the book, with the speaker looking for common ground with Adonis, finding empathy in their shared experiences:

In the locker room your makeup runsabout the authorin the shower like blood from a wound,

but not everything you scrub will come

clean. I can read the marks you bear, speak

the shame you know but can’t articulate.

Like you, I approach men looking to be made

whole in their embrace. I can read these marks

to you as well. In fact, we share them. (60-1)