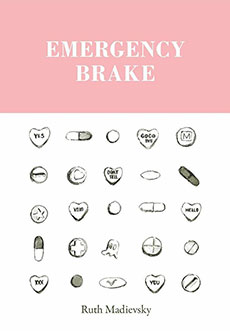

A Review of Emergency Brake

by Ruth Madievsky

Portland, OR: Tavern Books, 2016.

80 pages. $17 (paperback)

Ruth Madievsky’s debut collection, Emergency Brake, investigates the boundaries between experience and recollection, myth and memory, the car screeching to a halt and the tree it is veering towards. Better put by Madievsky herself, it is “… the space between two objects, two people / who aren’t touching” and “the distance between the drive to the hospital / and the hands in our chests” (58). With a keen eye for metaphor and compelling, voice-driven narratives, Madievsky creates episodes of surprising disjunctive association and beauty. These are poems that metamorphose, extend, and investigate the limits of the body and how it holds together in the aftermath of distress.

In the opening poem, “January,” the speaker finds the New Year arriving to applause as “the hinges of everything alive / opened like fruit.” This celebratory tone is quickly abandoned as the speaker challenges T.S. Eliot with their own interpretation of the cruelest month, stating that “… January unpeeled inside me / like a nicotine patch … ” (11). Reading this collection is like riding shotgun with an acquaintance who is recounting a past relationship. There’s an air of protective suspicion in the speaker’s voice, a privacy in the poems that isn’t keeping the reader at bay, but is instead engaging fully in the mystery, beauty, and healing power of art making. The speaker’s body becomes an ominous bedtime story in which a presumed lover is made to “dress up / as the fire-breathing dragon,” (12) and the unspecified relationship is summarized via polarities — the speaker and the “you” fit on a single spoon “like we were coconut extract / or a bump of cocaine” (11). This battle between what one desires and what one needs from a partner is a pendulum swinging through the collection, and the residue of drugs, sex, DNA, and stardust hang thick over every page.

Though the events of the relationship are guarded by nimble metaphors and turns of phrase the tension and anguish of working through trauma are palpable and play out across the seasons. In “One Spring,” the speaker, on recalling a boyfriend, hears “the washing machine / trying to beat the blood out of my dress” (45), while in “Mountain,” “July is giving me / the kind of look / that makes me think / it might throw something” (47). The poems don’t follow a strict chronology but they do fall in line with the stages of grief, with the speaker experiencing everything from shock, anger, denial, and guilt, to hope and acceptance. The book is organized into two numbered sections, the latter opening with the poem “Night,” in which the speaker asserts that night, “is a story the hypothalamus tells itself” (35). This mirrors and inverts the book’s first poem, recalling again the speaker’s body becoming a bedtime story in which an ex-lover is cast as a dragon. The designation of the dragon in the story could be seen as a metaphorical repurposing of pain, transformed into anger and directed at the recast, fire-breathing body of the former lover. However, this anger “like everything else … / felt good until it didn’t” (12). By the second section of the collection the speaker seems resolved to articulate the past rather than internalizing it. “Night” ends with the conclusion that “night is a mouth becoming a door” (35), implying, perhaps, that as the body releases the deadbolt of pain the past can finally exit.

This is not an easy journey, though. The four poems sharing the title “Shadowboxing,” peppered throughout the collection, provide the reader with a window into the speaker’s battle with herself, fighting anger and guilt, recalling the tragic and personal while trying to let go of the urge “[t]o address someone I love / the way a knife is thrown at a tree” (13). The tree and the violence against it are packed with allusions, summoning images from the Garden of Eden, Daphne fleeing Apollo, or even the magician’s assistant, tied there with an apple on their head — all of these archetypes erotic, dangerous events whose magic is used for the entertainment of others. “[M]y body [is] a basketball hoop / a flat tennis ball, broken beer bottle,” (28) the speaker says. “I am both the box / and the box-cutter” (40) and a bomb that needs to be re-wired (38). Whatever the catalyst that ended the relationship, the result is that the speaker finds her body irreversibly transformed and out of her control. It is only through boxing with her shadow — the shadow being simultaneously insufferable for the metaphorical weight it carries, and inseparable from who she is — that the speaker can reckon with the constant attacks against her body.

In “Halloween,” the speaker’s boss flippantly remarks that the speaker’s enjoyment of the holiday reflects an equal enjoyment of kinky sex. The speaker doesn’t respond, but instead finds consolation in holding tight to her beer bottle, ignoring the laughter of her co-workers and escaping into her thoughts. Yet, the objectification continues. A man asks for the speaker’s mouth “like he was asking to bum a cigarette” (35), and when looking at another man the speaker instead sees “a handprint on a window. / Something inside me / scattering like deer” (37). Constant sexual affronts leave the speaker shaken and seemingly lacking trust in both strangers and friends. As a result, the speaker develops an acute awareness of distance, both physical and emotional. In “The Space Between,” the speaker, during a ride in a cab, is keenly aware of the space between herself and the driver, which she fills with nervous laughter to avert attention from being in the car with a strange man. In “Tuning Fork,” a male friend tells the speaker that he’s sick of being careful in his sexual interactions, leading the speaker to recall that she was once “… tree-ringed / by the man who took my silence / to mean yes” (42).

While the presumed narrative might appear to be the center of these poems, Emergency Brake’s core might actually be Madievsky’s masterful control of language and timing, her knowledge of when and for how long to let the reader into a narrative. This is a poet who knows the limits of what the reader can take and what the speaker is willing to reveal. In “Mountain,” the speaker jokes with her brother about an anesthesiologist’s wife who doesn’t know she’s being abused (48), a moment that perhaps highlights how often we joke about the things that make us most uncomfortable. In a world of contemporary media and popular culture, joking has become one of our strongest defense mechanisms: it distances us from the violence in our world and downplays the need for responsibility. Madievsky is a careful and purposeful poet, though, whose use of humor only adds to the strength of this collection. While the speaker’s jokes are addressed to other people within the poems, it’s often hard not to feel as though the speaker is turning to the audience and breaking the fourth wall, as in the poem “Nesting Dolls,” where the speaker quips that “It’s going to be all rapid-fire dick jokes / and YouTube videos of Celtic dance / from here on out” (55).

Notably, the book’s consideration of the body is manifold, its metaphors and observations ranging from the material body to microscopic and celestial ones. The speaker views her own body as everything from a suitcase to a pillbox, vegetables, watermelon, and deer. In like manner, the speaker contemplates, in varying linguistic configurations, about how “even inside a burning body, / all that we love / becomes the atoms / of something else” (36). This shifting of scale, this collapsing and expanding of the body, allows the speaker an even further investigation into the physical, chemical, and emotional proximities that exist between human bodies and objects. When the speaker’s grandfather goes to the hospital for an operation his body is transformed into “a space station for someone else’s hands,” and the speaker desires to “hold him / like he is something other / than a mucus membrane. / Like maybe the planet inside him is Pluto, / like it’s not really a planet at all” (43). In this manner, Madievsky poses the dilemma of being human, being corporeal, yet mortal and finite. These poems brim with hope and sheer determination, illustrated by the speaker’s declaration that, “you are not going to fade out like a cough” (57). By the time we reach the closing poem, “Because it’s October,” the speaker is “feeling like a real person / with real skin, real hair, / a real heart” (67).

Every poem in this collection, dear reader, is worth your time, every question raised herein worth your consideration, because you live in the world of this speaker, a world that is being reconstructed by a distinct and powerful voice. Early on, the speaker expresses the concern that “… every poem I write / is an act of public indecency” (48). Because this book chooses to speak it is one of the most decent acts that can be offered to a world that largely ignores its most serious problems. The greatest act of public indecency occurs when we choose not to speak. The danger of exposure is present but the vulnerability expressed in these poems is a staggering act of bravery and invention. Poetry is the contextualization of passion and generosity, and the greatest form of generosity is creative. In a world that is always taking, and taking particularly from women, to give one’s words as a metaphorical body is a necessary and admirable allowance. Beyond its skillful use of language and surprising metaphors, the biggest accomplishment of Emergency Brake might be in its revelation that, despite all life throws at us, “[t]he human heart will remain / the size of two fists” (21).

about the author