Translator's Note

When I moved from the south of Italy to the south of France in September of 2024, the first thing I disinterred from my suitcase was a trade copy of Dante’s Inferno I purchased in the summer of 2022 in Firenze during what seemed like an interminable train delay at Santa Maria Novella. Watermarks from sweating bottles of frizzante spotted its cover like wintertime’s lunar halos made earthly and fixed, and a bit of paper hung out of the thick text as it would a tongue bereft of words though not yet tired of speaking. I pulled the scrap and it fell to rest upon a pile of unmatched socks, face up with some text (a date, a question, a library record) I evidently wrote but hardly remember:

19 October 2023

What the hell am I supposed to find here?

Biblioteca Nazionale di Napoli - Landino, Comento, 1481, Niccolò di Lorenza

della Magna, Firenze, SQ16L10.

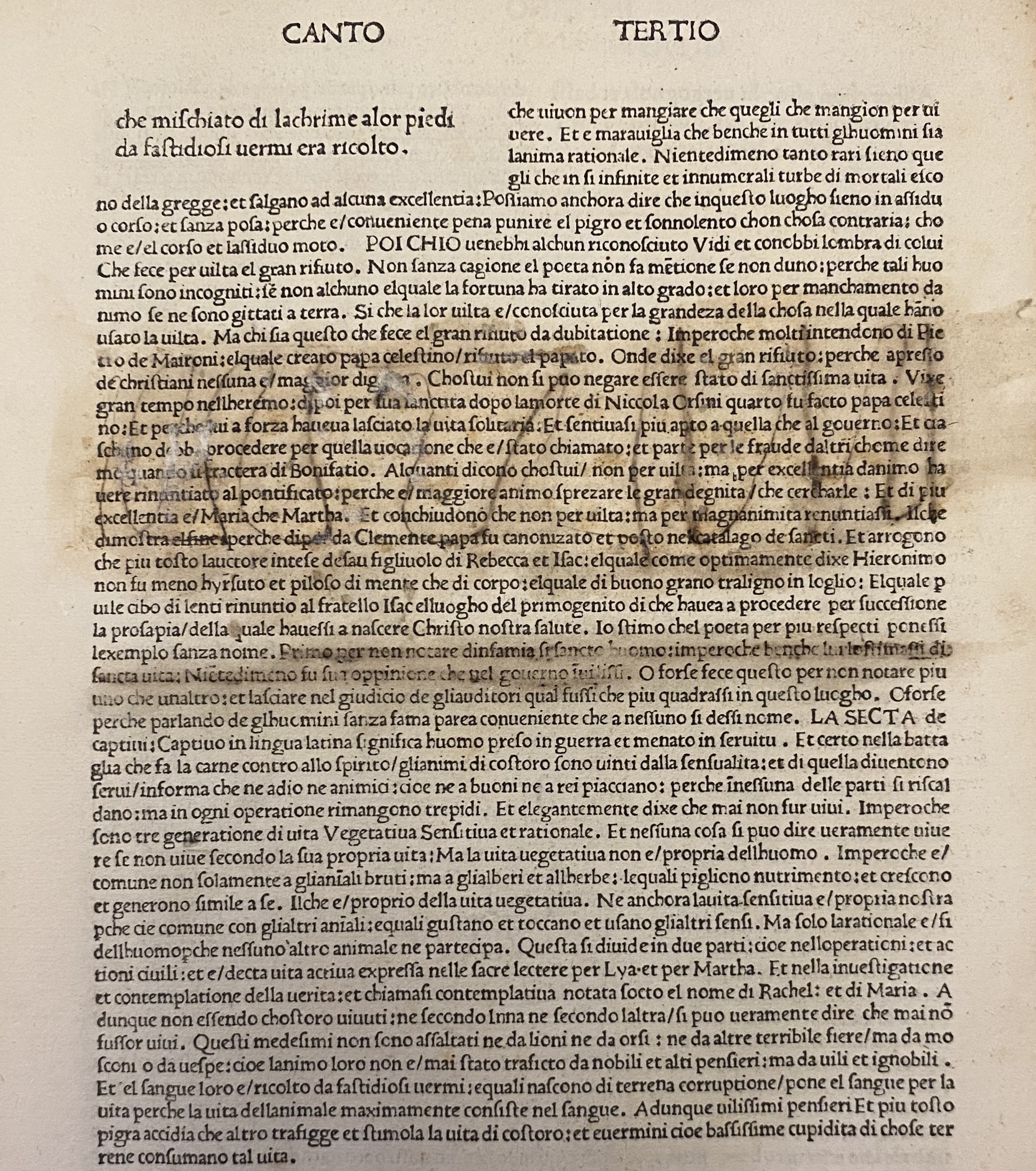

I am writing this, now, in April of 2025 and I continue to pose questions, neither to myself nor the library, nor my home university, nor the funding body that supported my research, but to the incunabula catalogued as SQ16L10, the copy of the 1481 Niccolo di Lorenza della Magna printing of Cristoforo Landino’s Comento from which I have made these translations and from which I am translating a new Commedia.

These days, though, I am gentle, asking after a relation in the conditional mood “what would you like to reveal today?” where revelation is close kin to finding again (re-finding, or in a literal translation to Italian, ritrovare) what was always already there to begin with.

I first encountered SQ16L10 in the fall of 2023 when I was a Fulbright researcher in Naples, Italy. I arrived to the Biblioteca Nazionale di Napoli unsure of what I might find in their collections, but when presented with SQ16L10, I noticed first its state of disrepair; second, the proliferation of diverse annotating hands. These readers made corrections, lists of popes and monsters and sinners, cross-references between the three canticles of the Commedia, and finally, censorships consistent with the Inquisition’s 1612 Index Expurgatorum.

These redactions captivated me not only historically, but also aesthetically as examples of mark making: as that which is left behind by the presence of a reader. The redactions took multiple forms: a blotting out of single sentences; a pen stroke across multiple lines of text; residue from an obfuscating page glued in place. The acts themselves not only affected their intended “target,” but also inflicted collateral damage upon surrounding “innocent” text in secondary marks I would come to call “exit wounds” in my research notes.

The translations presented here are inflected with the material life of SQ16L10. Translation choices I have made in the poem are results not just of Landino’s extensive commentary, but especially of the resonating losses of the original. Likewise, the redacted commentary is, in one sense, meant as a memorial to that which is lost by obliteration, both materially (passages of text) and figuratively (histories, lives, attitudes and opinions that challenge—in their beliefs, actions, or their very existence—the state and its institutions of power).1

1. Lost & Found

My relationship to Dante’s Commedia spans decades. Older than the age of my most enduring friendships, il rapporto mio with Dante’s cosmological frame (especially Hell) has grown since my teenage years. Over these twenty-some seasons, I’ve collected Danteisms in popular culture, in science fiction, in graphic novels, and in poetic interpretations. An enduring favorite of such examples remains Caroline Bergvall’s performance VIA, which catalogues and recites the first tercet of the Divina Commedia 48 times across 48 different translations (including a new, sonic translation derived from the performance itself). The famous opening, Nel mezo del camino di nostra vita mi ritrovai peruna selva obscura che la diricta via era smarrita (quoted here as it is printed in SQ16L10) in multiplying iterations, transforms into meditation on the continuum of lostness (“era smarrita”) and re-foundness (“mi ritrovai”) foundational to the entire story of the Commedia.

Because Dante’s Italian is foundational to modern Italian, both smarrita and selva have Dantean meanings in modern Italian: selva, not only a wilderness but a state of confusion;2 smarrire, not only to lose one’s way, but to lose one’s (figurative) vision.3 This opening tercet thus articulates the central idea of the Commedia: the encounters with loss that give boundary to human subjectivity; the necessity to accept, rather than deny or cheat, this atmosphere of grief as that which makes us uniquely ourselves. In this sense, I know Inferno especially as a poem of leaving, of lostness, of dispossession, amidst trusting “some noble star or other thing”4 with the always-collaborative task of the re-finding.

At the beginning of Inferno III, Dante-pilgrim5 arrives at the gates of hell where he reads those words of a “senso duro,” a hard sense, a difficult thing, heavy and serious. This inscription–“hard to hear and hard to know”–that concludes with the iconic, “Lasciate ogni speranza voi chentrate” is most usually translated as something like, “Abandon all hope, you who enter.” The gate is an address that directly instructs its reader in the imminent transformation that awaits them: it is not simply hope that will be lost, but rather an entire ontological stance. Io sono un portale, the gate says—I am a portal through which the old self must be shed and mourned before taking on the journey ahead. It is a portal both described and crafted: the internal rhyme of lasciate and chentrate binds these two actions eternally. Simply put, to enter is to leave behind.

I cannot read or translate this passage without zooming in on Lasciate, a form of lasciare. Lasciare can mean to leave behind, to “lose” in this sense; it is the verb I’ve used for bad boyfriends (I left him); for luggage (I left it). It is the word that is in some cases equivalent to “let” as in, let [go of] or release.6 In Lasciate, I imagine Dante-pilgrim letting himself up for the journey ahead in the same breath as I imagine Dante-poet surrendering himself to the project. I imagine the dispossession of lasciare directly applied to Dante-poet’s exile from his beloved Florence. Ho lasciato Firenze, he might say.

Lasciare in this usage differs slightly from another kind of loss present in this inscription: perdere, the verb one would use in a contemporary setting for being physically lost in a city or missing a train.7 However, one can also “perdere la ragione,” (to lose reason) and “perdere l’anima” (to lose the soul, to be damned). If lasciare is an intentional casting off; perdere implies the misfortune of getting off the track of a map, a timetable, the course of reason, or the lineage of goodness. Thus a reader can know Dante’s laperduta gente not as the collective left behind or released, but rather those who, by weakness or by will, have lost their way.

Perdere and smarrire are wholly absent from Inferno XX, however, forms of lasciare appear four times with four different connotations. Here, lasciare is the verb Dante uses to describe what Manto did to her bones (left them), what both Amphiaraus and the “wicked unnamed” did to their stations in life (abandoned them) and finally, in a usage I have not yet mentioned here, what God has done to the compassionate reader to enable them to absorb the full spectrum of human folly (marks them)8. In this canto, to be “marked so” is to be left with a remainder which is not precisely that which is lost, but that which is gained through the experience of loss.

For the dannati of Inferno XX their fate, like all the others’, is lostness. The uniqueness of the seers’ eternal lostness is that theirs has a particular poetry as punishment for their presumptive re-foundness (their divinations and attempted knowledge of their future lot). Such a punishment is one that Dante himself has great compassion for (and for which is reprimanded by Virgil)9 for the very fact that he knows the sting of lostness (exile and dispossession of place), the desire for foundness (the return), and the temptation of the use of craft (poetic and otherwise) for a re-foundness ahead of schedule.

2. Grief People

The first time I read Inferno III in incunabula form was in 2021 at Harvard University’s Houghton library. At this point in my PhD, I had not yet studied paleography and my Italian was laughable. I made no research notes about where or when it was printed. I made no transcriptions. I found the cursive font representing words in a language I barely grasped inscrutable. I made no note of the catalogue number. I took only a few photographs which have since been lost in a smashed, un-backed up iPhone.

In 2021, just two years before my Napoli note, I very truly had no idea “what the hell” I was supposed to find here in this text and in this particular collection. Seeking any glimpse of meaning, I seized upon Inferno III with its recognizable repetition of “Per me” in the opening tercet:

Per me si va nella citta dolente

Per me si va nelletherno dolore

Per me si va tra laperduta gente

Today I can reasonably guess (from my best recollection) that this particular incunabula was printed in cancelleresca, a Renaissance font based upon cursive script used by “men of letters” during Dante’s own time. What I remember most, however, is the way my unfamiliarity with the language and its most basic representation (the letter form) produced possibilities for equivalency beyond the sense-making of the word or phrase or sentence. Rather, in my search for meaning I translated the vertical and horizontal as a simultaneous cluster linked by sound and the visual information of the printed letter “e,” rather than a linear sequence. Thus, where laperduta gente has an English equivalent close to “the lost people” or “the lost ones,” in my simultaneous translation cluster, these “gente” are not only “perduta” (lost) but also “dolore” (pained) and “dolente” (sorrowful). In my simultaneous translation cluster, these “gente” become unmoored from verbal sense-making boundaries, instead entering into an excessive relationship with the signs that surround them: they are now a fourth, oltre thing beyond the meaning of the words themselves. In this case, they are thus the Grief People, where grief is the relation I choose for the overlapping experience of pain, sorrow, and the multiple lostnesses expressed in the famous inscription.

More than this, these Grief People articulate something central to Dante’s Commedia as a whole, for to grieve is to leave someone or something behind (lasciare); to have lost something or someone irrevocably (perdere); to lose one’s sense of self; to be beside oneself (smarrire). To be amongst Inferno’s dannati is to be lost in all senses of lasciare, perdere, smarrire. To be enthralled in the valences of grief is, too, to be at once totally lost and totally vulnerable to the re-finding.

__________________________________________

1 My thoughts on erasure are especially inflected by Solmaz Sharif’s enduring essay “The Near Transitive Properties of the Poetical and the Political: Erasure” in The Volta, M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong!, Jenny Sharpe’s Immaterial Archives: An African Diaspora Poetics of Loss, and Kinohi Nishikawa’s “Black Arts of Erasure” in ASAP/Journal

2 From Lo Zingarelli: selva, “Moltitudine grande e confusa di persona, cosa”

3 From Lo Zingarelli: smarrire, “non trovare più, non sapere più dove si trova qualcosa, gli occhiali, le chiavi di casa” and “non sapere piú qual è la via giusta” and “confondere, turbare” and finally, a definition that derives from the Commedia itself, “Offuscarsi, dello sguardo.”

4 See Inferno XXVI, 22-24: “perché non corra che virtù nol guidi / sì che, se stella bona o miglior cosa / m'ha dato 'l ben, ch'io stessi nol m'invidi” which I translate as, I home my hurried genius / such that it does not run / unless virtue directs it / but if some noble star / (or better thing) gave me / the will, I’d not fear / to use it.

5 Note that critics and scholars of Dante often make the distinction between Dante-poet (the human being who wrote the Commedia) and Dante-pilgrim (the fictional, if somewhat autobiographical character who undergoes a journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise).

6 From Lo Zingarelli, lasciare can mean “cessare di tenere, di stringere” and “Andarsene da un luogo , temporaneamente o definitivamente” and in two figurative usages, “Lasciare il mondo: morire” and Lasciarci la pelle, morire”

7 From Lo Zingarelli, perdere can mean “Cessare di avere, di possedere qualcosa che prima si aveva o si possedeva” and “Non avere più qualcosa definitivamente o temporaneamente, restare senza qualcosa” with examples: “in autunno le piante perdono le foglie; ho perso il sonno per colpa sua.”

8 In an early interjection, Dante makes the apostrophe: “Reader, if God marks you so, take the fruit this lesson offers and ask yourself how I could possibly keep my face dry when I saw our human image drawn like so (I couldn’t)” upon seeing these damned who are “battered” and “distorted” and whose “sorrow-sodden, twisted fronts make their asses shores to their rivers of tears.”

9 See Inferno XX, 27: “Ancor se' tu de li altri sciocchi?” which I translate as: “Tell me you’re not like / these future-seeing fools?”

about the author